My only fashion construction endeavor was at age 15. Due to the lack of particular camp attire, I set out to sew the Communist grey Polish Girl Scouts uniform required for summer camp. I enrolled in a continuing education sewing class and was determined to make the uniform from a simple sewing pattern. After struggling for weeks, the result was a fashion wreck. The skirt pulled and the hem was uneven with bumpy stitches. I felt defeated and muttered to myself, thank God we have department stores and boutiques!

My only fashion construction endeavor was at age 15. Due to the lack of particular camp attire, I set out to sew the Communist grey Polish Girl Scouts uniform required for summer camp. I enrolled in a continuing education sewing class and was determined to make the uniform from a simple sewing pattern. After struggling for weeks, the result was a fashion wreck. The skirt pulled and the hem was uneven with bumpy stitches. I felt defeated and muttered to myself, thank God we have department stores and boutiques!

All the other girls had their mother sew their uniform or hired someone to make them one. Not me. I tenaciously sewed my own crooked version.

My struggle to create a simple uniform gave me a deep appreciation for fashion designers. They sketch, choose fabrics and then complete a garment through patience, tenacity and vision. It also made me enamored of 20th century couturiers such as Balenciaga, Dior and Chanel who created meticulous works of wearable art.

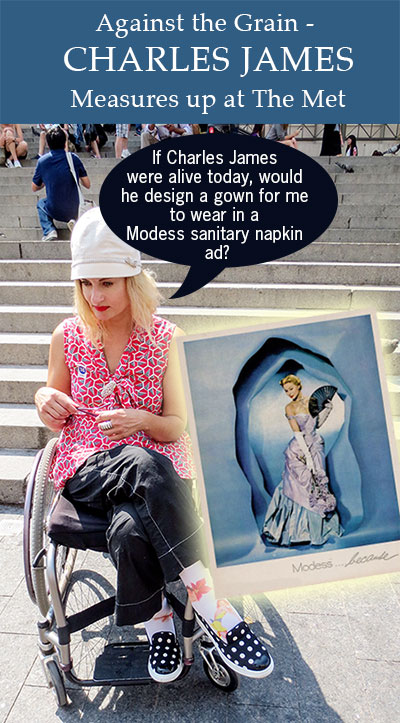

One other such couturier who deserves mention is Charles James. A retrospective of his work is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY through August 10th.

I’m in front of the Met’s Charles James exhibit. I wish I could have worn a gown, but it wasn’t conducive for someone in a wheelchair. Instead I am wearing a Goorin Bros. hat, Mata Traders Fair Trade top, Anthropologie pants, pin-up girl socks, Hogan polka dot slip-on sneakers.

Born in Britain in 1906 to a wealthy family, James began his career as a milliner before permanently settling in NY in the late 1930s. Over four decades his oeuvre included ready-to-wear, couture, children’s clothing, furniture design and accessories. But it was his sumptuous couture gowns, commissioned by socialites, which garnered him the most accolades. Charles James is known for his feats of engineering in his approach to creating couture. His technique was totally unconventional yet it always worked due to his painstaking technical process.

Charles James with models at a 1950 show. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; © Bettmann/Corbis.

The exhibit is housed in two sections on two floors. The first floor gallery exhibits 15 ball gowns representing the zenith of his career in the 40s and 50s. Each gown stands on a platform with animated video imagery and projectors designed by architectural firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R). The gowns then appear on a screen along with descriptive scrolling text and a 3D rendering deconstructing the pattern pieces. The video installation enables us to see the individual pattern pieces and then through 3D visualization and animation puts the pattern pieces together one by one on the mannequin. A robotic arm moves up and down the gown beaming an ultrasound light revealing on screen the blocking net, grosgrain and boning used to support the bodice. I marveled at the high tech display designed for each gown. This was one of the most remarkable fashion exhibits due to the digital recreation of the minutiae that went into creating these gowns. A layperson with a rudimentary understanding of pattern making and design, could appreciate the excruciating detail behind these architectural, sculptural forms.

The exhibit is housed in two sections on two floors. The first floor gallery exhibits 15 ball gowns representing the zenith of his career in the 40s and 50s. Each gown stands on a platform with animated video imagery and projectors designed by architectural firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R). The gowns then appear on a screen along with descriptive scrolling text and a 3D rendering deconstructing the pattern pieces. The video installation enables us to see the individual pattern pieces and then through 3D visualization and animation puts the pattern pieces together one by one on the mannequin. A robotic arm moves up and down the gown beaming an ultrasound light revealing on screen the blocking net, grosgrain and boning used to support the bodice. I marveled at the high tech display designed for each gown. This was one of the most remarkable fashion exhibits due to the digital recreation of the minutiae that went into creating these gowns. A layperson with a rudimentary understanding of pattern making and design, could appreciate the excruciating detail behind these architectural, sculptural forms.

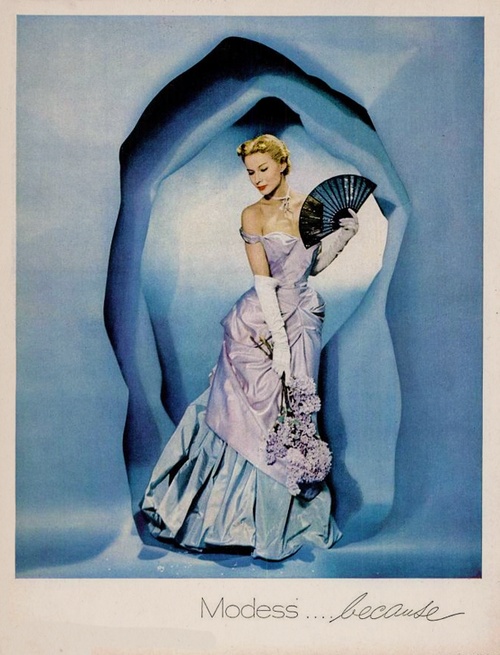

Finding humor in life and things is my raison d’être. When I saw this gown which first appeared in a 1948 ad campaign for Modess® sanitary napkins, I laughed out loud in the hushed exhibit hall. The accompanying text quoted James, “so that any woman at a different moment can imagine herself as a Duchess.” Modess (sanitary napkin) Duchess, that is! The tag line for the product was “Modess… Because.” BECAUSE, when my monthly curse arrives, the last thing I want to feel is like a Duchess swaddled in 10 lbs. of satin fabric. All I want to wear is a pair of stained sweats grasping chocolate cake wrapped in bacon. Most amusing is how this subject was never discussed, but suggested through the display of a Georgia O’Keefe-esque back drop evoking the layers and folds of a woman’s you-know-what.

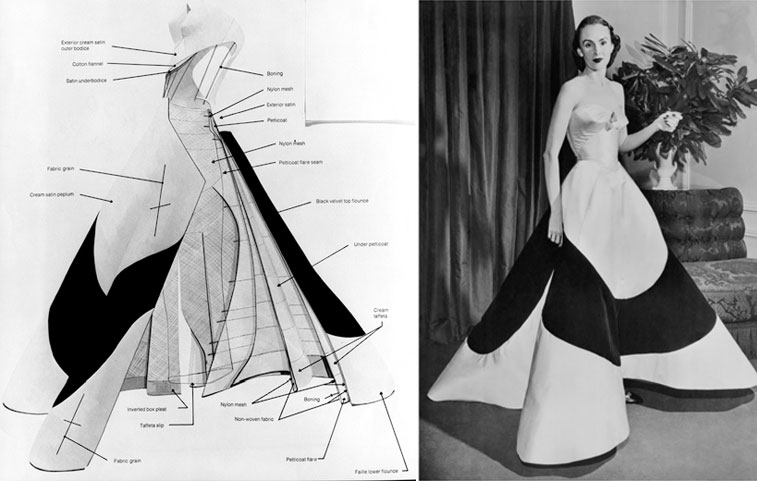

To comprehend the genius that was Charles James, one should scrutinize his iconic 1953 “Clover Leaf” ball gown designed for Mrs. Randolph Hearst (Austine) for the President Eisenhower inaugural ball. James designed many of his gowns on custom built plaster of Paris mannequin forms, as garment industry dress forms did not meet his standards. As is common practice of fashion designers, the design process begins by preparing inexpensive muslin fabric by plotting grain lines, then draping, pinning, clipping and basting the fabric onto the dress form. The muslin fabric simulates expensive fabric later cut into the pattern pieces. This 4-quadrant gown required an incredible 30 pattern pieces. He was known to be a perfectionist, sometimes taking 12 hours to finish just one seam. This pattern making feat earned him a reputation for being a garment engineer rather than a traditional couture dressmaker. He bucked traditional couture draping and pattern making, thereby creating his own vernacular.

To comprehend the genius that was Charles James, one should scrutinize his iconic 1953 “Clover Leaf” ball gown designed for Mrs. Randolph Hearst (Austine) for the President Eisenhower inaugural ball. James designed many of his gowns on custom built plaster of Paris mannequin forms, as garment industry dress forms did not meet his standards. As is common practice of fashion designers, the design process begins by preparing inexpensive muslin fabric by plotting grain lines, then draping, pinning, clipping and basting the fabric onto the dress form. The muslin fabric simulates expensive fabric later cut into the pattern pieces. This 4-quadrant gown required an incredible 30 pattern pieces. He was known to be a perfectionist, sometimes taking 12 hours to finish just one seam. This pattern making feat earned him a reputation for being a garment engineer rather than a traditional couture dressmaker. He bucked traditional couture draping and pattern making, thereby creating his own vernacular.

The Clover Leaf gown dissected and worn on the right by Mrs. Randolph Hearst (Austine). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art ©.

Clover Leaf gown as seen at the exhibit with digital monitor on the lower left. A study in muslin on the right. Photos courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art ©.

Evening Dress, 1948 – Black silk satin and black silk velvet

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Millicent Huttleston Rogers, 1949 (2009.300.734)

“Butterfly” Ball Gown, ca. 1955 – Brown silk chiffon, cream silk satin, brown silk satin, dark brown nylon tulle – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Fund, 2013 (2013.591)

Downstairs on the ground floor in the newly inaugurated Costume Institute’s Anna Wintour Costume Center, visitors are introduced to James’ earlier works including day wear-dresses, suits and coats. The adjoining room features his sketches, drawings, dissected mannequin forms, hats, children’s clothing and pattern pieces.

My favorite dress in this gallery is the Ribbon Dress of 1938-1940 which is constructed using actual ribbon, 6 inches at the hem and thinner at the waist.

Watch this video to see how the “Clover Leaf” gown was created.

My other favorite piece is this 1937 “Evening Jacket” made of satin and down. Was this beautiful jacket a precursor to the mass market, puffy suburban North Face jackets? Conversely, Comme des Garcon’s Rei Kawakubo reinterpreted puffer wear for the ultra-stylish.

As skilled a couturier as Charles James was, he lacked business acumen. Given his 40 year career, he only produced about 2000 gowns. His obsessiveness to detail, his ego, irascibility and breaches of contracts led the IRS to shut down his business in 1958. Even though he was notorious for severing ties with friends and patrons, he still designed for a few of his acolytes. Ultimately, he became destitute and died of pneumonia at his home at the Chelsea Hotel in 1978.

The early years – child’s jacket, framed pattern, petticoat scaffolding that Charles James constructed over a mannequin.

Though the show was curated beautifully, the exhibit on the first floor was dimly lit. If not for the detailed monitors describing the colors of the gowns, I would not have been able to decipher the color nuances. The integration of digital technology in explaining and illustrating Charles James’ revolutionary garment construction and composition was genius. This aspect set it apart from other costume exhibits and most certainly updated the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibit of 1982. Charles James would have heartily approved of such progressive technology exploring the intricacies of his mathematical and analytical mind at work. Kudos to the Met for taking an exhibition of the past and making it relevant for now and the future.